Provider Reimbursement System

View Adobe Acrobat Version | Download Adobe Acrobat Reader

Letter to Mental Health Stakeholder, June 2007

Table of Contents

Public Consulting Group, Inc. could not have conducted this study or produced this report without the help and support of a number of individuals and organizations. It is with gratitude that we acknowledge the following people and institutions:

Mr. Barry Brauth of the New York State Office of Mental Health played a critical role in helping us gather necessary data and in providing guidance throughout the project. Thanks also to Martha Schaefer Hayes, Deputy Commissioner of the Office of Financial Management, for her support, to the division staff, including Joyce Billetts and Gwen Diamond, and to all other New York State staff who met with us and worked to provide us with data.

We appreciate the time and effort of all the individuals who attended the two stakeholder meetings on January 3 and 5. Attendees represented the following organizations: Behavioral Health Services North, Builders for the Family & Youth of the Diocese in Brooklyn, Inc., Children’s Aid Society, Coalition of Behavioral Health Agencies, Inc., Community Health and Behavioral Services, Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors, Inc., Family Counseling Center of Fulton, Federation of Mental Health Centers, Inc., Greater New York Hospital Association, Healthcare Association of New York State, Institute for Community Living, Inc., Long Island Consultation Center, Inc., Mental Health Providers of Western Queens, Inc., New York Association of Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services, New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation, New York Psychotherapy and Counseling Center’s, New York State Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, Northside Center for Child Development, Northwest Community Mental Health, Putnam Family and Community Services, Inc., Rockland County Department of Mental Health, Schenectady County, St. Mary’s Hospital (Amsterdam), St. Vincent’s Catholic Medical Centers, and Upstate Cerebral Palsy.

- We also appreciate the willingness of the following providers to host us on our provider visits:

- Bleuler Psychotherapy Center, Inc.: Executive Director John Rossland

- F.E.G.S: Senior Vice President Amy Dorin and Chief Operating Officer Jonas Waizer

- Institute for Community Living, Inc.: Chief Operating Officer Stella Pappas and Associate Chief Financial Officer William Adler

- Builders for the Family & Youth of the Diocese in Brooklyn: Executive Director Donna Corrado

- Metropolitan Center for Mental Health: Executive Director Andrew Pardo

- St. Vincents Catholic Medical Centers: Kim Pagan, Vice President of Finance

- Horizon Health Services: Executive Director Anne Constantino

- North Star Behavioral Health Services/Citizens Advocates: Director Jim Brooks

In addition to those named above, many other staff members from each of the providers participated in our visits, and we thank them all. Their input proved invaluable to this study.

Executive Summary

The 2006-2007 Enacted Budget directed New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS OMH) to conduct a study of the mental health reimbursement system. The budget language stated:

For services and expenses associated with a study to review the current system of financing and reimbursement of mental health services provided by clinic, continuing day treatment and day treatment programs licensed under article 31 of the mental hygiene law, and to make recommendations for changes designed to ensure that the financing and reimbursement system provides for the equitable reimbursement of providers of mental health services and is conducive to the provision of effective and high quality of services. Such study shall be coordinated by the commissioner of the Office of Mental Health and shall be completed and submitted to the legislature no later than March 1, 2007.

Public Consulting Group, Inc. (PCG) was engaged by NYS OMH to conduct this study. New York State currently uses a funding and reimbursement methodology for their clinic, continuing day treatment (CDT) and day treatment programs that includes the use of a regional fee schedule for recognized services (the base rate) with the addition of provider specific supplemental payments (known as add-ons) to compensate providers for the costs of providing services. This system was established in 1991, and at the time it was a creative solution that provided the funding needed to meet the growing demand for and cost of these services. With the passage of time, however, the existing funding and reimbursement system has become antiquated and is not able to keep pace adequately with the needs of the providers and their consumers.

Based on this study, PCG has concluded that the current system of financing outpatient mental health services using an add-on structure should be replaced with a more equitable and more rational system of payment. The current system is outdated, inequitably funded and is based on a rate structure that has outlived its usefulness.

The COPs/Non-COPS structure that has been used for nearly two decades has resulted in provider payments that vary considerably (by over $200 a unit after cost outliers are removed), and these payment variations cannot be uniformly explained by differences in case mix or service intensity. In fact, at times the same service is reimbursed at different rates based solely on the facilitys license. Overall, reimbursement for facilities licensed by NYS OMH is divorced from reimbursement for facilities providing the same or similar services under licenses from the Department of Health (DOH), the Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (OASAS) or the Office of Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities (OMRDD). This discrepancy in reimbursement methodology is particularly striking given that, in some instances, the same individuals are served by all of these facilities. The irrational nature of the current reimbursement system is in part of a function of reimbursement and licensing freezes around which providers have learned to work.

What is needed is a complete overhaul of the current payment system. However, no changes to the reimbursement methodology for outpatient mental health services can be done without considering New York States overall health care policy goals. In writing this report, we understand that our study is narrowly focused, but that any solutions would have to include a much broader perspective of the states Medicaid reimbursement system as a whole.

NYS OMH Service Delivery Models and Reimbursement Rates

The current Medicaid reimbursement structure for outpatient mental health services includes basic components: a Medicaid base rate and supplementary payments. The base rate is determined in one of two ways. For free standing providers (Article 31) it is determined regionally with providers in the New York City metropolitan area receiving a higher rate than providers in Upstate New York. Hospital (Article 28) base rates are determined on a cost related, provider specific basis composed of an operating component capped at $67.5 and an uncapped capital component. There are three main supplementary payments, or add-ons:

- Comprehensive Outpatient Programs (COPs),

- Non-COPs, and

- Community Support Programs (CSP).

This study focuses on the COPs and Non-COPs add-ons. However, the State also needs to update the way the base rate is developed as well. The designation of COPs or Non-COPs plays a significant role in determining a providers available revenue and in many cases its expenditures. Historically, COPs providers were the providers who received state aid in the 1980s. Today, the COPs designation translates to increased revenue and increased regulatory obligations. COPs providers must adhere to nine specific regulations that include the provision of free care and 24 hour services and the ability to intake consumers from inpatient or hospital settings with 5 business days.

Non-COPs providers are those who did not receive state aid in the 1980s. While they do not have to adhere to the same regulations as COPs providers, they are only expected to adhere to four (4) of the nine (9) specific regulations for which they receive a Non-COPs add-on to help them cover the cost of providing mental health services. The Non-COPs add-ons tend to be nominal compared to the COPs add-on.

Community Support Payments (CSP) fund community based mental health programs that serve the severely and persistently mentally ill (SPMI) population. CSP add-ons deliver community supports such as psychosocial clubs.

Whether they are provided in clinic or hospital settings, outpatient mental health services in New York State include the following program models:

- Clinic treatment: Traditional outpatient therapy for children or adults, which includes clinical support services, health screening, symptom management and medication therapy.

- Continuing Day Treatment (CDT): Mental health services for adults who need help developing the skills necessary for independent living; CDT visits last longer than clinic visits and occur more often.

- Day Treatment: Mental health services for children who need help acclimating to or re-entering a traditional education setting. Day Treatment visits last longer than clinic visits and occur more often.

The New York Medicaid State Plan authorizes reimbursement for specific services for each of these program models.

Analysis of NYS OMH Data

This report relied on several sources of quantitative data, including:

- Consolidated Fiscal Reports (CFR)

- Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS) claims data

- Institutional Cost Reports (ICR)

- Patient Characteristics Survey (PCS) Data

The main themes include:

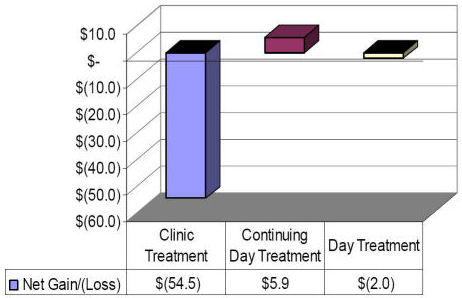

- Clinic programs shows considerable aggregate losses of $54.5 million, while Day Treatment shows a small deficit of $2.0 million and CDT programs show gains of $5.9 million.

- Eighty nine (89%) of the deficits incurred in the clinic are attributable to 10% of the provider population. However, it is not clear if this phenomenon is due to data quality problems, actual provider performance or a combination of both.

- The ninety percent of the provider population represents 309 programs and accounts for $11.0 million in deficits.

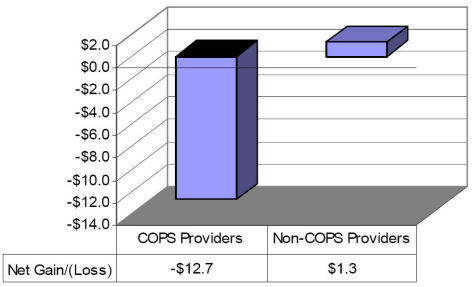

- COPs providers generate almost twice as much revenue per unit as non-COPs providers but COPs providers expenditures are twice as high leading to slightly greater losses and higher costs than Non-COPs providers.

- COPs providers in the clinic program represent 80% of the providers, render 80% of the services but generate 90% of the Medicaid revenues due to the COPs supplemental payments. Although this is the case, the COPs providers have the highest deficits.

- Variances in revenue and costs are significant between COPs and Non-COPs when comparing clinic programs, but are not as significant in Day Treatment or CDT Programs, which do not utilize an add-on reimbursement rate.

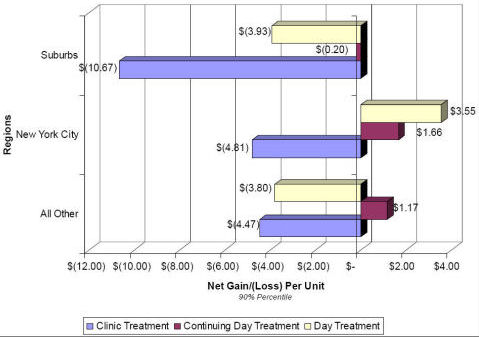

- Net gains and losses are heavily influenced by where a provider is located.

- Variations between providers costs and revenue indicate huge differences in how providers are controlling costs and billing revenue sources.

- The effects of size and location on provider costs and revenue vary and do not follow a consistent pattern.

Findings and Conclusions

Based on our review, PCG has concluded that the current system of financing and reimbursement must be overhauled completely. Changes to the system should be guided by the physical and behavioral needs of Medicaid enrollees receiving services and the research about the most effective models of care. Any restructuring should be done with the goal of creating a system that is more equitable across the provider community and aligned with the states mental health and overall health care goals. Our Findings and Conclusions are summarized below.

Findings

Finding 1: Reimbursements, costs and deficits vary substantially among providers.

There is substantial variance in the reimbursements providers receive and in the costs and deficits providers report. The reimbursement variance is attributable to the COPs, Non-COPs and CSP add-ons as well as the inconsistent COLA adjustment for some providers. Specifically, reimbursements for services vary by hundreds of dollars from provider to provider:

- Continuing Day Treatment, 1 hour service for units 1-50: $12.65 to $225.32

- Clinic Regular: $49.64 to $567.25

- Day Treatment, full day - $70.93 to $332.83

Costs per unit of service vary considerably with some providers expenses reported as being thousands of dollars higher than those of other providers. Even when the top 5% and bottom 5% outliers are removed from the analysis, because we question the accuracy of the reported data, expenses vary over $200 per unit.

The average cost per unit follows:

- Continuing Day Treatment-$19.28

- Clinic Regular-$122.55

- Day Treatment-$67.40

Provider gains and deficits vary considerably with some providers reporting over $13 million in losses while others report over $2 million in net gains. While some of this variation may be attributable to poor data, when outliers are removed losses and gains ranged from ($1.5 million) to $2.3 million.

Finding 2: The current reimbursement system is complex and is not transparent or easily understood by providers.

Providers feel the system is arbitrary, has negative cash flow impacts on their business practices and is difficult to manage. For example, providers are required to estimate and set aside any over allocation of rate supplement funds that could be recouped by the state on an annual basis.

Finding 3: New York State collects a significant amount of detailed data from providers.

Through the CFR and ICR reports and the Patient Characteristics Survey, the State collects a significant amount of data from providers that can be utilized in the development of a reimbursement methodology and later in ongoing reimbursement updates. Although the infrastructure is comprehensive, there are some issues of data quality and comparability that would need to be addressed if the data were to be used for this purpose.

Finding 4: Providers recognize the importance of Quality. Providers are conducting various continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiatives and are measuring various outcomes.

Many providers are taking part in the states continuous quality improvement (CQI) initiative for which they receive additional reimbursement. Additionally, many providers have established their own quality initiatives. The degree to which quality measures are implemented varies by provider, with many larger providers employing a dedicated quality assurance staff and smaller providers relying on administrators to fulfill that role.

Finding 5: There are several cost drivers that significantly impact clinic, CDT and day treatment.

Provider costs are impacted by many factors that include, but are not limited to: geographic location, client need and characteristics, staffing models, productivity and no-show clients, provider size, and the provision of non-reimbursable services, as well as serving Medicaid Managed Care and uninsured consumers.

Finding 6: In total there was a 50.7 million net deficit for the agencies and programs included in this study. (346 out of approximately 455 in the New York State mental health reimbursement system).

Providers reviewed reported an overall program deficit on their cost reports. The $50.7 million includes state and local net deficit funding of $25 million reimbursed to the providers included in this study. (The deficit is $75.7 million when the state and local net deficit revenue is removed.) Even when the outlier providers (10% of the top) are excluded, the remaining 90% of providers have an $11.4 million net deficit for all of the programs combined. The loss appears to be based on a combination of uncompensated care and limits and rate inadequacies by Medicare, managed care companies, and other insurance programs.

Finding 7: Providers are performing Medicaid outreach services to increase client enrollment in Medicaid.

Although they are not required by NYS OMH and are not currently billed to Medicaid administration, some providers perform outreach services to clients, including providing Medicaid informational material, assessing clients for Medicaid eligibility, and helping set up appointments with Medicaid eligibility workers.

Finding 8: New program funding, changes to state law, and changes to the SCHIP program will reduce the size of the un- and underinsured population.

Recent changes in funding, law and policy in New York State will impact the availability of funding to support mental health services. Timothys law the expansion of Child Health Plus and the removal of administrative obstacles to Family Health Plus will increase the amount of private insurance and Medicaid/State Childrens Health Insurance Plan coverage available to mental health clients and thereby decrease the pressure of the un- and underinsured population on mental health providers.

Finding 9: Providers cited difficulty in recruiting appropriately licensed staff, particularly in specialty areas.

Providers say they have a difficult time recruiting appropriately licensed staff, particularly in specialty areas such as childrens psychiatry and bilingual staff. Providers cited low salaries/salary competition, tough work environments and fewer licensed providers than actual demand as impacting their ability to recruit and retain staff. The staff recruitment problem is exacerbated among providers who serve large Medicaid Managed Care populations because many Managed Care Organizations have higher standards for provider qualifications than the state Medicaid program. These problems are compounded by the fact that rates have not kept pace with increasing costs.

Finding 10: The existing reimbursement system has not kept up with changes in the delivery system. It does not have a process in place to adequately adjust the baseline from which funding add-ons were originally calculated.

The initial funding calculations that determined the amount of the provider-specific add-on payments were largely based on the overall financial performance and funding sources of the provider in the 1989 base year and its designation as either a COPs or Non-COPs provider. There is no mechanism within the system to rebase these add-on payments to maintain a consistent relationship between costs and funding at a provider level. As a result, inequities among like providers have become significant over an 18 year period.

Finding 11: Providers indicate that the distinctions differentiating providers have narrowed since the original funding formula was developed.

Over the years, services offered by various providers have become more comparable, consumers served and payer types have become more consistent across providers. As a result, anecdotal evidence suggests that the distinctions that originally separated some types of providers have disappeared.

Finding 12: If the resources in the existing system were redistributed, a significant increase in the clinic base rate could be financed.

The current rate structure roughly reflects the average cost of services but is disproportionately distributed. Hypothetically, an average per visit increase of approximately $70 could be supported if all current add-ons were evenly distributed.

Finding 13: Low Medicaid managed care reimbursement and the subsequent addition of the COPs add-on managed care reimbursement has eroded the financial health of providers and created a duplicative, costly state payment mechanism.

Individual providers must negotiate the Medicaid managed care rate with the managed care organization. For COPs providers, the COPs add-on amount is paid separately to the provider for outpatient services provided to a Medicaid managed care consumer. This system exacerbates financial strain on the system both by providing a reportedly insufficient payment to providers and by eliminating state savings gained through a managed care capitation.

Conclusions

As New York State moves forward in considering whether to restructure its Medicaid reimbursement methodology for outpatient mental health services, there are a number of items the state should consider. First and foremost, the state should consider how outpatient mental health services fit into the states overall health care policy objectives. Second, it should create a system that is based on validated, consistent and up-to-date data. By ensuring consistent data collection and using the most current data available, the State of New York could create a reimbursement system that is based on current costs. The state can also use this opportunity to tie the reimbursement methodology more closely to the mission and goals of NYS OMH.

The new system should also give due consideration to the following reform principles and ideas for redistribution of resources:

- Medicaid payments should address the reasonable and necessary cost of providing services to Medicaid enrollees.

- Medicaid payments must take into account the multiple needs of individuals requiring mental health services, including integration with general health care, substance abuse, and mental retardation services.

- The payment method should be built on an econometrically sounds basis, taking into account differences in provider service type, case mix, service intensity, geography and volume.

- Financial incentives must be aligned across facility licenses and settings.

- Add-on payments should be eliminated. The savings should be reinvested into a new payment structure that takes case mix into consideration and that would apply to all providers.

- NYS OMH should consider the use of more appropriate, HIPPA-compliant codes, where the type and amount of services delivered are consistent with CPT-4 definitions.

- Further consideration should be given to the development of incentive payments that tie to measurable indicators of quality, such as outcomes accountability, individualized services, and overall responsibility for the client.

- The state needs to recognize the need for indigent care and should consider developing an Indigent Care Pool, which would address issues related to net deficit financing and wrap-around services. Indigent care payments to providers should be based on the relative percentage of uninsured patients in their caseload.

I. Introduction

The 2006-2007 Enacted Budget directed New York State Office of Mental Health (NYS OMH) to conduct a study of the mental health reimbursement system. The language stated,

For services and expenses associated with a study to review the current system of financing and reimbursement of mental health services provided by clinic, continuing day treatment and day treatment programs licensed under article 31 of the mental hygiene law, and to make recommendations for changes designed to ensure that the financing and reimbursement system provides for the equitable reimbursement of providers of mental health services and is conducive to the provision of effective and high quality of services. Such study shall be coordinated by the commissioner of the Office of Mental Health and shall be completed and submitted to the legislature no later than March 1, 2007.

In December 2006, NYS OMH contracted with Public Consulting Group, Inc. (PCG) to conduct this study.

Significance of Study

Outpatient mental health services play a critical role in the overall health of individuals and in the health care delivery system. Estimates of prevalence suggest that during any given year, one quarter of the population suffers from some kind of mental health problem, including depression, anxiety and more serious conditions. Yet many people do not have access to mental health services when necessary due to multiple factors including lack of insurance coverage and the unavailability of services in some areas. Primary care physicians fill some of the gap, but they have neither the time nor, in some cases, the expertise to keep people out of jeopardy. During 2006, while over 5 million New Yorkers were on the Medicaid or SCHIP roles, only 11% received any kind of mental health service. One third of those mental claims were merely prescriptions unaccompanied by either a specialty practitioner or a mental health diagnosis.

Outpatient services are the least expensive, most highly utilized mental health services. Nevertheless they continue to be used by only a fraction of those who need them and according to a review of MMIS data, are rarely overused. Fewer than 4% of New York Medicaid recipients use more than 40 visits a year; only 1% use more than 60.

The current reimbursement system for mental health outpatient services is a complex matrix that is not working. It was crafted over time with federal and state approval and has not kept up with current needs. Care must be given to do no harm to consumers and to ensure that changes do not create an environment that results in increased homelessness, arrests, or hospitalization. This work should continue with attention given to redesigning the reimbursement system in concert with the states reform agenda.

No changes to the reimbursement methodology for outpatient mental health services can be done without considering New York States overall health care policy goals. Outpatient mental health services represent a small slice of the overall mental health landscape, which in turn constitutes only one piece of New Yorks Medicaid and health care environments. These pieces interact daily on the patient level, as co-morbidity is a significant issue for many mental health consumers. As a result, it would be imprudent to make changes to the outpatient mental health reimbursement system without looking at a more integrated financing system for Medicaid. In writing this report, we understand that our study is narrowly focused, but that any solutions would have to include a much broader perspective.

History

The Medicaid base rate for clinic, day treatment and continuing day treatment (CDT) services was developed in the early 1980s using a regional fee. The state determined a cost-based regional fee using information from providers who received state aid. Budget constraints resulted in the state funding the Medicaid rate at 75% of the calculated cost of services (fee).

The Comprehensive Outpatient Programs (COPs) Medicaid rate add-on was implemented in 1991 as a Medicaid enhancement project. Providers that received net deficit funding prior to the implementation of COPs saw that state funding converted to Medicaid funding and increased by 10%. This new system increased federal participation in the mental health programs. Nine criteria were established to ensure that COPs providers complied with these requirements (See Section II for more information). At a minimum, COPs providers receive the following Medicaid rate components:

Medicaid Base Rate + COPs add-on

For all services where the COPs rate applies the minimum, maximum, and average rate are in the chart below:

COPs Rate

| Min | Avg. | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDT | $0.20 | $25.69 | $106.36 |

| Clinic Treatment | $6.79 | $121.86 | $300.00 |

| Day Treatment | $1.58 | $42.74 | $194.66 |

| *Minimum rates do not factor in zeros | |||

| **Averages do not factor in zeros | |||

The COPs add-on amount increased several times between 1991 and 2003 for Cost of Living Adjustments (COLA), rate cap adjustments and additional conversions of state funds. The Medicaid base rate did not increase from 1991 to 2000. The following table details the changes in the COPs add-on that have occurred over time:

| Date | Description | Clinic | CDT | Day Treatment | COLA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4/91 | Initial conversion of Article 31 agencies | $52,831,463 | $9,783, 604 | $2,608,961 | $5,691,970 | $70,915,999 |

| 4/92 | Expand COPs to Article 28 agencies | $29,175,584 | $5,402,886 | $1,440,770 | $3,143,327 | $39,162,566 |

| 4/93 | Aggregate individual COPs rates into one combined rate | $20,501,762 | $3,796,623 | $1,012,433 | $2,208,824 | $27,519,641 |

| 4/95 | Increase of rate cap to $83.20 | $1,3247,292 | $2,453,202 | $654,187 | $743,320 | $17,098,002 |

| 4/98 | Allocation of the 2.5% COLA | $2,499,788 | $671,984 | $141,734 | $150,599 | $3,464,105 |

| 4/00 | Conversion of previously allocated non-COPs funds | $170,930 | $44,547 | $- | $6,464 | $221,941 |

| 5/00 | Increase of rate cap to $100 | $6355249 | $34,734 | $10,213 | $194,946 | $6,693,141 |

| 5/01 | Increase of rate cap to $200 | $23580026 | $317,539 | $383,854 | $747,534 | $25,665,350* |

| 4/03 | Conversion of Reinvestment funding to COPs | $9473969 | $613,902 | $715,793 | $- | $11,821,066* |

| 4/03 | Rate disaggregation and increase of rate cap to $300 | $118576 | $- | $- | $- | $118,576 |

| 4/03 | Conversion of Shared Staff to COPs | $7,812,148 | $647,893 | $457,971 | $- | $8,918,012 |

| Grand Total | $165,766,787 | $13,983,310 | $7,425,916 | $12,886,984 | $174,111,983 | |

* Totals include rate increases associated with PHP and IPRT services, which are outside the scope of this study. M/

Source: Fiscal Brief: Comprehensive Outpatient Programs (COPs), New York State Conference of Local Mental Hygiene Directors, Inc. October 2004. Retrieved December 7, 2006, from http://www.clmhd.org/resources/resources.aspx#604 ![]() .

.

In the following years, Non-COPs providers sought and received an add-on component. This add-on component is generally less than the COPs add-on. At a minimum, Non-COPs providers receive the following Medicaid rate components:

Medicaid Base Rate + Non-COPs add-on

For all services where the Non-COPs rate applies, the minimum, maximum, and average rate are in the table below:

Non-COPs Rate

| Min | Avg. | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDT | $1.37 | $4.66 | $7.73 |

| Clinic Treatment | $2.39 | $5.41 | $7.73 |

| Day Treatment | $1.94 | $4.45 | $5.80 |

| *Minimum rates do not factor in zeros | |||

| **Averages do not factor in zeros | |||

Over time Non-COPs providers have sought to equalize their total Medicaid rate with the rate received by the COPs providers. Both COPs and Non-COPs providers have sought Medicaid rate increases.

Focus of the Report

This report focuses on the reimbursements, costs and deficits associated with the current mental health Medicaid reimbursement methodology. The study considers the costs associated with three mental health services:

- Clinic

- Day Treatment

- Continuing Day Treatment (CDT)

The study aims to determine whether the current Medicaid reimbursement system is equitable and effective. Additionally, the study focused on recommending changes to the current system to ensure equitable reimbursements, an effective system and the provision of high quality service.

Study Methods

PCG employed a hybrid study approach, incorporating elements of a descriptive study with some elements of a case study. PCG used numerous data sources that provided both quantitative and qualitative data about the current reimbursement system. This hybrid method allowed for the use of diverse information streams and a comprehensive analysis of the current Medicaid reimbursement system.

For the descriptive portion of the study, NYS OMH provided quantitative data in several different forms:

- Consolidated Fiscal Reports (CFR)

- Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS) billing data

- Patient Characteristic File

- Institutional Cost Reports (ICR)

These data sources allowed us to compare costs and units of service across providers.

Although this study is not written as a case study, PCG conducted several interviews, focus groups and site visits to gather qualitative data. These data collection techniques are often used in case studies. For this study, PCG collected qualitative information from multiple sources, including:

- State level key informant interviews and meetings

- Two stakeholder meetings for providers and trade associations

- Meeting in Albany, NY on January 3 for stakeholders from Upstate New York.

- Meeting in Manhattan on January 5 for stakeholders from the New York City metropolitan area.

- Eight provider visits with key informant interviews

- Bleuler Psychotherapy Center, Inc., Forest Hills, Queens January 11

- F.E.G.S, New York City and Suburbs January 16

- Institute for Community Living, Inc., Brooklyn January 17

- Builders for the Family & Youth of the Diocese in Brooklyn, Far Rockaway January 17

- Metropolitan Center for Mental Health, Manhattan January 18

- St. Vincents Catholic Medical Centers, Harrison January 18

- Horizon Health Services, Buffalo January 19

- North Star Behavioral Health Services/Citizens Advocates, Malone January 19

The qualitative data collected at the meetings and site visits described above provided crucial information that could not be discerned from financial and billing data alone.

In addition to the quantitative data provided by the state and the qualitative data gathered by PCG, this report relies on several pre-existing sources of information about the Medicaid reimbursement methods currently employed by NYS OMH. These sources included:

- New York State regulations

- New York State Medicaid Plan

- Previously conducted reports and articles

PCG and NYS OMH also developed a provider survey as part of this project. However, following input from provider organizations, it was determined that the short time frame of the project was not sufficient to allow for accurate responses or a representative level of participation. As such the survey was not conducted.

Organization of the Report

This report is organized to provide the reader with all necessary information to understand the current Medicaid reimbursement system used for clinic, continuing day treatment and day treatment services. Data analysis and key findings follow the background information. The report concludes with PCGs finding and conclusions, as well as some reform principles that should be considered going forward.

Below is a brief description of each section of the report:

Section I provides a historical context for the report and an explanation of the study focus and methodology.

Section II provides a more in-depth look at the current reimbursement methodology, breaking the fee structure down piece by piece. Elements discussed in this section include:

- Article 31 (free standing provider) agencies and Article 28 ( general hospital provider) agencies, as defined in Section II;

- Regional variations;

- COPs and Non-COPs designations; and

- Medicaid Managed Care

Section II also provides a high level look at the mental health services included in this study and of the Comprehensive Outpatient Programs (COPs) designation. This section defines clinic, continuing day treatment and day treatment services and outlines the regulations that mandate services at COPs providers.

Section III provides detailed information about the qualitative and quantitative data used in this study including an overview of the stakeholder meetings, provider visits and an in-depth data analysis.

Section IV outlines the Findings and Conclusions that surfaced as a result of this study. This section also includes a discussion of the key considerations and the potential obstacles associated with alternate reimbursement methodologies.

II. NYS OMH Service Delivery Models and Reimbursement Rates

In this section we will provide the following:

- Overview of NYS OMH clinic, day treatment, continuing day treatment Medicaid base rate (fixed fee) methodology;

- Overview of COPs, Non-COPs, and CSP supplementary add-on methodology;

- Detailed description of clinic, day treatment, and continuing day treatment allowable services; and

- Detailed description of clinic, day treatment, and continuing day treatment Medicaid rates.

Reimbursement Methodology Overview

Two major components of clinic, day treatment and continuing day treatment program reimbursement are:

- Fairly uniform fixed fees (Medicaid base rate) for units of services and

- Highly variable, provider-specific supplementary payments.

Medicaid Base Rate Fixed Fees

New York State utilizes a fixed Medicaid base rate for reimbursing clinic, continuing day, and day treatment services. Fixed fees offer incentives to providers to deliver more units of a service, if the payment per unit of that service is greater than the providers marginal or incremental cost of delivering an additional unit of that service (e.g., the hourly salary and fringe benefits of the professional delivering it). If the payment per unit of service is less than the incremental costs of delivering it, providers have no financial incentive to deliver the service, therefore jeopardizing access in the short term. If the payment per unit is greater than the providers incremental costs, but still less than the providers total (incremental plus fixed) costs per unit of a service, access to and/or quality of the service may be sufficient in the short term but still be in jeopardy over the long term.

Fixed fees encourage cost-effective management practices, such as increasing clinician productivity ratios by adjusting hours of operations to the needs of the community, using contracted versus salaried staff if it is conducive to clinician productivity, adopting carefully researched approaches to reduce the no-show rate among clients, properly billing and pursuing recovery from difficult third party payers, etc. Many of these desirable practices are evident in New York State.

However, fixed fees do not encourage the expansion of services or other activities that would increase the providers costs without corresponding adjustments in fees. Fixed fees offer no assurance that providers will accept consumers without Medicaid or other insurance.

NYS OMHs fixed fees take into account many desirable treatment practices, such as optimum therapy session/visit duration, appropriate group therapy models, the involvement of family members and other collateral individuals in the care of the consumer, and reasonable limits on service volume. The fixed fees also take into account, to a degree, variations in regulatory requirements applicable to different types of providers; variations in the capital and labor markets associated with delivering care, such as the supply and demand for the skilled, dedicated professionals who deliver mental health services in communities throughout New York; and geographic variations within the State in costs, service availability, service volume, consumer mix, and other factors.

NYS OMHs fixed fees for clinic treatment are generally identical for children and adults, despite the substantial costs of child psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. New York does recognize a special program of day treatment for children that has its own reimbursement rules. Generally, fixed fees are identical for seriously and persistently mentally ill (SPMI) adults, non-SPMI adults, seriously emotionally disturbed (SED) children, and non-SED children.

Supplementary Payments

New York State utilizes supplementary add-ons to the Medicaid rate. The supplementary payments are determined using formulas that include the providers historical costs and net deficits as variables. There are large supplementary payments for Comprehensive Outpatient Programs (COPs) providers and smaller supplementary payments for Non-COPs providers and Community Support Program (CSP) services. Each component offers advantages and disadvantages that should be assessed individually, in combination and as they relate to the short- and long-term goals of the NYS OMH, the Governor and the State Legislature.

COPs and Non-COPs Providers

In return for the COPs reimbursement, COPs providers are required to adhere to the following regulations: 1

- Ensure access for individuals upon service availability; not on an individuals ability to pay.

- Provision of priority access to adults with serious mental illness or children with serious emotional disturbance.

- Provision of initial assessment to persons referred to inpatient or emergency setting within five business days.

- Agreement to engage with the LGU in annual planning activities.

- Assurance that services are provided to all individuals within a designate geographic area or target population for whom the COPs program is responsible as designated by the local governmental plan.

- Arrangement for the provision of 24-hour emergency services.

- Development of formal written agreements with inpatient services addressing access, case management, home care of other clinically necessary services.

- Creation of a consumer advisory board or inclusion of consumers on the governing body.

- Development of staffing patterns which take into account the cultural and ethnic background of consumers served.

Additionally, under Article 41 in 1984-85, one of the criteria for the initial COPs provider designation was that the provider received State funds.

Non-COPs providers also must adhere to certain regulations, including:

- Non-COPs providers must admit a client within 5 days of hospital discharge.

- Non-COPs providers will perform case management, when necessary.

- Non-COPs providers are not obligated to treat clients who are not insured or cannot pay the requisite fee.

Comprehensive Outpatient Program (COPs) supplementary payments are determined as follows:

- 2001 mental health grants are added to the deficit approved in the calculation of the COPs supplementary rate

- Mental health grant amounts are divided by the estimated annual number of Medicaid visits (average of the 3 most recent years/.909)

- An adjustment is made for Medicare/Medicaid crossover claims

- The supplement is subject to a cap of up to $300 per unit of service

The supplementary amount is applied to all outpatient claims, except for hospital-based providers where it is not applied to collateral, group collateral or home visits.

Since 2000, Non-COPs have received an add-on of 12.5%. This supplement is for a specific amount of units per service per year as determined by the Commissioner. Non-COPs providers must reimburse the state for any supplemental dollars received in excess of the threshold. COPs providers represent 80% of the clinic programs, 82% of the units rendered, and 90% of the Medicaid revenues.

Managed Care and Supplements

An increasing number of Medicaid recipients are enrolled in managed care organizations that receive Medicaid capitation payments for mental health services. Providers must seek Medicaid reimbursement through the Managed Care Organization (MCO) for these clients based on the requirements and payment methods of the MCO. Individual providers must negotiate the Medicaid managed care rate with the managed care organization. Reimbursement rates from MCOs are significantly lower than base rates used by states. For COPs providers, the state pays the COPs add-on amount separately (in addition) to the provider for outpatient services provided to a Medicaid managed care consumer.

Article 31/Article 28 Differences

Individual provider rates are further impacted by whether the provider is designated as an Article 28 or Article 31 provider. Article 28 providers are general hospital providers, defined in Article 28 of the Public Health Law, which are permitted to conduct an outpatient program for adults diagnosed with a mental illness and children diagnosed with emotional aberration in accordance with Part 587. Article 31 providers are free standing outpatient programs, pursuant to Article 31 of the Mental Hygiene Law, which are permitted to serve adults diagnosed with mental illness and children diagnosed with emotional aberration in accordance with Part 587. Article 31 providers have received annual cost of living adjustments on their fixed fees. Article 28 hospital based providers have lower fees because they have not received these COLAs but receive a cost-based rate which is still capped at $67.50, plus a capital pass-through. Since the cap has not been raised in almost 20 years, they now average less than freestanding providers. Article 28 Diagnostic and Treatment Centers (D&TC) receive the 1992 base rate, trended through 1995 and capped at the 1995 rate. Article 31 providers represent 82% of all clinic providers and 81% of Medicaid revenues.

CSP supplementarypayments

Community Support Payments (CSP) fund community based mental health programs that serve the severely and persistently mentally ill (SPMI) population. CSP rates are calculated based on:

- 1997-98 mental health aid grants

- Adjustments to grants based on percentage of services eligible for Medicaid reimbursement

- Adjustments to grants based on percentage of clients eligible for Medicaid

- Aggregation of all service units for clinic, continuing day treatment, and day treatment programs for children

- Computation of the average number of service units for the 3 years prior to the base year

- Division of the adjusted grant amount by the average number of service units

- Adjusted grant amount per unit is divided by 0.89

CSP rates vary based on provider. The table below illustrates the range in rate add-ons paid.

CSP Rate

| Min | Avg. | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDT | $11.10 | $53.38 | $170.73 |

| Clinic Treatment | $0.62 | $42.45 | $300.00 |

| Day Treatment | $4.24 | $25.70 | $117.47 |

| *Minimum rates do not factor in zeros | |||

| **Averages do not factor in zeros | |||

Clinic, Day Treatment, and Continuing Day Treatment Services

New York regulations state:

The purpose of outpatient programs for adults with a diagnosis of mental illness is the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness on an ambulatory basis. The goals of outpatient treatment for adults are to reduce symptoms, to maximize potential for recovery of meaningful social involvement to maintain the recipients capacity to function in the community, or when appropriate, to improve parental functioning while maintaining or restoring minor children to the care of the parent where feasible.2

NYS OMH providers are all tasked with the above policy. Provider types have similar goals, and some common aspects of service. During admission, all provider types are required to collect the same client information, including:

- Reason for referral;

- Primary clinical and service-related needs; and

- Admission diagnosis.

Also, clinics, day treatment for children, and continuing day treatment providers all offer the following services:

- Medication therapy;

- Medication education; and

- Symptom management.

Clinic Treatment

Clinic treatment consists of outpatient services for children and adults. These services are rendered face to face. The mission of clinics is to reduce symptoms, improve functioning and provide ongoing support. Upon intake, clinic clients are assessed to help identify mental health strengths and weaknesses. These assessments help drive treatment options.

Reimbursable services in a clinic setting: The following services are allowable for Medicaid Reimbursement:

Clinic Treatment Service Coverage

| For Adults | For Children | |

|---|---|---|

| Case management services |  |

|

| Clinical support services |  |

|

| Crisis intervention services |  |

|

| Family treatment services |  |

|

| Health screening and referral |  |

|

| Medication education |  |

|

| Medication therapy |  |

|

| Psychiatric rehabilitation readiness determination and referral |  |

|

| Symptom management |  |

|

| Verbal therapy |  |

|

All of the services listed in the chart except case management, crisis intervention, clinic support services, and family treatment services are mandated by NYS OMH for all clinics. Medicaid fees also apply to psychiatric rehabilitation readiness determination and referral services that are mandated by NYS OMH for clinics serving adults.

Clinic Reimbursement Methodology

The New York Medicaid program reimburses NYS OMH-approved mental health clinic treatment programs using fixed fees plus supplementary payments.

Units of services: Medicaid fees for clinics are set based on units of service and require face to face encounters with consumers. Medicaid usually reimburses units of services equally, whether they are health screening, case management, or any of the other NYS OMH-approved clinic service. Medicaid fees generally are identical for children and adults. NYS OMH has defined units of service in terms of duration and type of a face-to-face encounter, as follows:

- Brief visit: 15-29 minutes

- Regular visit: 30 or more minutes

- Crisis visit: 30 or more minutes

- Group therapy visit: 60 or more minutes, in groups consisting of 2 12 consumers

- Collateral visit: 30 or more minutes with someone other than the consumer, such as a family member, for a purpose directly related to the care of the consumer

- Group collateral visit: 60 or more minutes, in groups consisting of 2 12 consumers

Brief visits qualify for fees that are half of the fees for regular, crisis, and collateral visits. Group and group collateral visits of 60 or more minutes qualify for fees that are, per individual, about 35% of the fees for encounters of 30 or more minutes with one individual. Thus, an hour-long group visit with four to 12 consumers usually would generate more reimbursement than two regular visits of 30 minutes each.

Geographic variations: Fees for clinics vary based on where the clinic is located. Clinics located in metropolitan New York City (New York City, Long Island, Westchester, Putnam, and Rockland Counties) qualify for the highest fees. Clinics located in Central and Western New York State qualify for 90% of the highest fees. Clinics in the Hudson River Valley, as well as clinics that received no State aid for mental health services in 1984-85, qualify for 88.33% of the highest fees.

Clinic Treatment Programs

| Brief visit | at least 15 minutes no more than 29 minutes face-to-face one-on-one between recipient and therapist |

|---|---|

| Regular visit | at least 30 minutes face-to-face one-on-one between recipient and therapist |

| Crisis visit | at least 30 minutes face-to-face one-on-one between recipient and therapist |

| Group therapy | at least 60 minutes provided to and from 2 to 12 recipients per therapist(s) |

| Family visit | at least 60 minutes face-to-face one recipient, one or more of his or her family members, and therapist |

| Collateral visit | |

| a. Clinical support services | at least 30 minutes face-to-face between one or more collaterals and one therapist with or without a recipient |

| b. Family treatment | at least 30 minutes face-to-face among all the following: a recipient, one or more family members, and a therapist |

| Group collateral visit | |

| a. Clinical support services | at least 60 minutes no more than 120 minutes face-to-face services to more than one recipient and/or his or her collaterals. Such visit need not include recipent but shall not include >12 collaterals and/or recipients with a therapist |

| b. Family treatment | at least 60 minutes no more than 120 minutes face-to-face shall include services to more than one recipient. For each recipient participant, at least one family member shall participate. However, only one group collateral bill per recipient is allowed per day. Shall not include >12 participants, including recipents and family members |

Visits are defined as a face-to-face interaction between a recipient or collateral and clinical staff for the provision of service. A visit shall involve one or more required or additional services or any optional services approved by the Office of Mental Health.

Clinic Treatment Programs

| Fee Schedule | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Programs that Received State Aid 1984/1985 ( COPs) | Programs that Did Not Receive State Aid 1984/1985* (Non-COPs) | |||

| A 3 | B 4 | C 5 | ||

| Brief visit | $35.97 | $32.37 | $31.77 | $31.77 |

| Regular visit | $71.94 | $64.75 | $63.55 | $63.55 |

| Crisis visit | $71.94 | $64.75 | $63.55 | $63.55 |

| Group therapy | $25.18 | $22.66 | $22.25 | $22.25 |

| Family visit | Qualified family visits shall bill one regular visit and one collateral visit. | |||

| Collateral visit | $71.94 | $64.75 | $63.55 | $63.55 |

| a. Clinical support services | ||||

| b. Family treatment | ||||

| Group collateral visit | $25.18 | $22.66 | $22.25 | $22.25 |

| a. Clinical support services | ||||

| b. Family treatment | ||||

The Fee Schedule reflects the 2005/2006 Enacted State Budget

*Effective this year the Non-COPs providers will get the same base rate as the COPs providers

Day Treatment Programs Serving Children

Day treatment programs serve only children. These programs are designed to help juveniles with mental health illness acclimate to or re-enter educational settings. Day treatment is designed to provide a continuity of care once the client has been discharged from an inpatient setting. Services include social, vocational, and educational activities to maintain or enhance the functioning level of the child.

Payment amounts for day treatment providers vary based on the length and type of visit and whether the provider is located in New York City (the five boroughs). Providers that received no mental health state aid in 1984-85 receive the lower reimbursement amount regardless of their geographic location.

Day treatment services are used less frequently than clinic and continuing day treatment programs, based on the number of units reported in a year. Day Treatment services are provided face to face to clients.

Reimbursable services in day treatment programs for children: Medicaid reimburses for the following services:

Day Treatment Program Coverage

| Case management |  |

| Crisis intervention services |  |

| Health referral |  |

| Medication therapy |  |

| Social training |  |

| Socialization |  |

| Task and skills training |  |

| Verbal therapy |  |

Medicaid generally reimburses these services equally. All of these services are mandated by NYS OMH for all day treatment programs for children.

Day Treatment Programs Reimbursement Methodology

The New York Medicaid program reimburses NYS OMH-approved day treatment programs for children based on allowable numbers of hours of day treatment services, plus supplementary payments. The hourly payment amounts vary based on the geographic region of the State and the hours of services provided in a day. Day treatment programs qualify for supplementary payments in the same way as clinics and CDTs.

Units of services: Medicaid fees for day treatment programs for children are for visits and full or partial days. Medicaid usually reimburses units of services equally, whether they are health referral, medication therapy, or any other NYS OMH-approved day treatment program service. NYS OMH has defined units of service in terms of duration and type of visit, as follows:

- Full day: 5 or more hours

- Half day: 3-5 hours

- Brief day: 1-3 hours

- Collateral visit: 30 minutes or more

- Home visit: 30 minutes or more

- Crisis visit: 30 minutes or more

- Preadmission visit, full day: 5 or more hours

- Preadmission visit, half day: 3-5 hours

Half day visits are generally reimbursed at half the amount of full day visits and brief day visits at one-third the amount of full day visits. Collateral visits generally are reimbursed at the same amount as brief visits.

Day Treatment Programs Serving Children

| Fee Schedule | ||||

| For Programs that Received State Aid 1984/1985 | For Programs that Did Not Receive State Aid 1984/1985 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A6 | B7 | |||

| Full day visit | at least 5 hours | $70.01 | $67.68 | $67.68 |

| Half day visit | at least 3 hours no more than 5 hours | $35.01 | $33.84 | $33.84 |

| Brief day visit | at least 1 hour no more than 3 hours | $23.34 | $22.52 | $22.52 |

| Collateral visit | at least 30 minutes | $23.34 | $22.52 | $22.52 |

| Home visit | at least 30 minutes | $70.01 | $67.68 | $67.68 |

| Crisis visit | at least 30 minutes | $70.01 | $67.68 | $67.68 |

| Pre-admission visit-full day | at least 5 hours | $70.01 | $67.68 | $67.68 |

| Pre-admission visit-half day | at least 3 hours no more than 5 hours | $35.01 | $33.84 | $33.84 |

Geographic variations: Day treatment programs for children located in New York City that received State aid for mental health services in 1984-85 qualify for fees that are about 3.5% higher than other programs.

Continuing Day Treatment

Continuing day treatment (CDT) programs serve adults, typically those with a long-standing mental illness. Many CDT clients have been hospitalized in a psychiatric setting but have been discharged and transitioned to live in the community. The goal of CDT is to help clients develop the skills necessary for independent living while maintaining a continuity of care. CDT services are provided face to face to clients.

Reimbursable services in a CDT setting: The following activities are included in continuing day treatment services:

Continuing Day Treatment Coverage

| Activity therapy |  |

| Case management |  |

| Clinical support services |  |

| Crisis intervention services |  |

| Health referral |  |

| Medication education |  |

| Medication therapy |  |

| Psychiatric rehabilitation readiness determination and referral |  |

| Rehabilitation readiness development |  |

| Supportive skills training |  |

| Symptom management |  |

Seven of these services are mandated by NYS OMH for all CDTs.

Continuing Day Treatment Programs

| Continuing day | RAMS at least 1 hour no more than 5 hours per recipient per day |

| a. Regular visit | |

| b. Crisis visit | |

| Collateral visit | at least 30 minutes no more than 120 minutes face-to-face interaction between one or more collaterals and one therapist with or without a recipient. |

| Group collateral visit | least 60 minutes no more than 120 minutes shall represent service to more than one patient and/or his or her collaterals. Such visits need not include patients but shall not include >12 collaterals and/or recipients in a face-to-face interaction with a therapist. |

Continuing Day Treatment Reimbursement Methodology

The New York Medicaid program reimburses NYS OMH approved continuing day treatment (CDT) programs based on allowable numbers of hours of CDT services, plus supplementary payments. The hourly payment amounts vary based on the geographic region of the State and the hours of CDT services per month per client. CDTs qualify for supplementary payments in the same way as clinics.

Units of services: Medicaid reimburses CDT programs for visits and allowable numbers of hours. CDT regular visits are usually between 1 and 5 hours, collateral visits are 30 minutes to 2 hours, and group collateral visits are 1 to 2 hours. Medicaid usually reimburses hours equally, whether they are health screening, case management, or any of the other NYS OMH-approved CDT services, and whether they are for regular, collateral, or group collateral visits. But payments per hour are about 26% lower for CDT programs that provide 80 or more hours of services per month per client than CDT programs that provide 51 to 80 hours per month per client.

Continuing Day Fee Schedule

| A8 | B9 | C10 | Non-COPs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service hour 1-50 | $13.20 | $11.88 | $11.88 | $11.88 |

| Service hour 51-80 | $10.45 | $10.45 | $10.45 | $10.45 |

| Service hour beyond 80 | $7.70 | $7.70 | $7.70 | $7.70 |

Geographic variations: Payments are about 26% higher for CDT programs in metropolitan New York City that received State aid for mental health services in 1984-85 and provide 1 to 50 hours per month per client of services, as compared with CDT programs in the same area that provide 51 to 80 hours per month per client. The payments are 11.5% higher under the same circumstances outside metropolitan New York City.

Although there are several similarities between the three provider types, the current Medicaid reimbursement system is built on the differences among the providers. These differences come in the form of a COPs or Non-COPs designation and the services offered by each provider.

III. Analysis of NYS OMH Data

Qualitative Data Analysis

PCG facilitated two stakeholder meetings and conducted eight provider visits in order to obtain qualitative data for this study. The qualitative data was not meant to be all-encompassing; instead it provided much-needed context through which we could examine the quantitative data.

Because PCG only visited 8 providers in a system of 455 statewide the information we collected from these visits cannot necessarily be generalized to the entire provider community. Similarly, information from the COPs and Non-COPs providers we visited cannot be relied upon to be representative of all COPs or Non-COPs providers in their region or of their size. As a result, PCG has chosen not to include detailed information gathered at the provider visits and stakeholder meetings: We do not want to present the experiences of a few providers as those of the system as a whole.

Instead, this section provides a high-level overview of themes that emerged from our qualitative research. The themes are broken down into three categories:

- General Themes: These are the issues, thoughts, statements and concerns that cut across provider type and agency location.

- COPs Themes: These subjects were repeated by several COPs providers.

- Non-COPs Themes: These subjects were repeated by several Non-COPs providers

General Themes

- Providers do not believe there are significant differences in the services provided by COPs and Non-COPs providers. This sentiment was repeated by COPs and Non-COPs providers alike.

- The client population and range of services provided have changed dramatically since the early 1990s. Mental health referrals are increasing as hospitals and correction facilities discharge clients to mental health providers.

- The severity of the mental health issues being addressed at clinics has increased over the past 15 years.

- The staffing structure i.e. unionized vs. non-unionized, salaried vs. fee-for service is the biggest cost differential between providers.

- In the clinic setting, serving children is more costly than serving adults.

- Most providers are committed to quality assurance measures, although there is a wide variety from one provider to the next in the scope of quality measures used.

- No-shows are problem for all providers, and while many providers are taking steps to lower their no-show rates, there is no magic bullet that will eliminate this issue.

- The rates paid by most Medicaid Manage Care Organizations are too low to support the services provided.

- Staff recruitment and turnover is a universal problem, although the specific recruitment issues that providers have vary from place to place.

- Medicaid rates only pay for direct service, but there is a significant amount of administrative and other work that must occur outside of the visit in order to provide the consumer with a high level of care. This work is not accounted for in the Medicaid rate.

- A providers location impacts many factors: cost, consumer population, the need for bilingual services.

COPs Themes

- COPs providers uniformly stated that losing the COPs add-on would significantly reduce the number of services they offer.

- COPs providers believe their costs are higher because they are seeing more SPMI consumers than Non-COPs providers.

- Costs associated with administering the COPs program add to the overall cost of services at COPs agencies.

- The COPs ceiling on the amount of add-on reimbursement a provider can receive in a year is problematic because it does not allow for caseload growth and because it causes some unpredictability in revenue.

Non-COPs Themes

- Although Non-COPs providers may not be required to meet some of the COPs requirements, many indicated that they do.

- Non-COPs providers do not believe there is a substantial difference in the number of SPMI consumers served by them than by COPs providers.

- Because Non-COPs providers do not have a financial safety net, they say they have adopted many cost-cutting measures, like having administrators fill two or more functions.

- Non-COPs providers fear that if a new reimbursement system is developed by NYS OMH that is closed to their participation, it will once again leave them behind by recreating a rate structure that they believe is inequitable.

PCG used a variety of data sources, described below, provided by NYS OMH to identify trends in cost and revenue based on a variety of factors, such as type of provider, location of provider, services offered, and consumer characteristics. This data is intended to illustrate, confirm and quantify the themes that were presented in stakeholder meetings and provider visits. We have identified some major themes and trends in the data below that indicate significant disparities in cost, revenue, gains and losses among providers. The main themes presented in this section include:

- Clinic programs shows considerable aggregate losses of $54.5 million, while Day Treatment shows a small deficit of $2.0 million and CDT programs show gains of $5.9 million.

- Eighty nine (89%) of the deficits incurred in the clinic are attributable to 10% of the provider population. However, it is not clear if this phenomenon is due to data quality problems, actual provider performance or a combination of both.

- The ninety percent of the provider population represents 309 programs and accounts for $11.0 million in deficits.

- COPs providers generate almost twice as much revenue per unit as non-COPs providers but COPs providers expenditures are twice as high leading to slightly greater losses and higher costs than Non-COPs providers.

- COPs providers in the clinic program represent 80% of the providers, render 80% of the services but generate 90% of the Medicaid revenues due to the COPs supplemental payments. Although this is the case, the COPs providers have the highest deficits.

- Variances in revenue and costs are significant between COPs and Non-COPs when comparing clinic programs, but are not as significant in Day Treatment or CDT Programs, which do not utilize an add-on reimbursement rate.

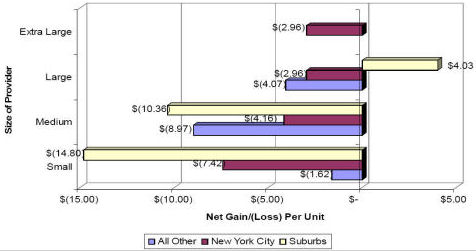

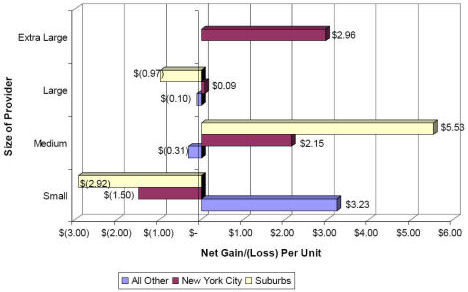

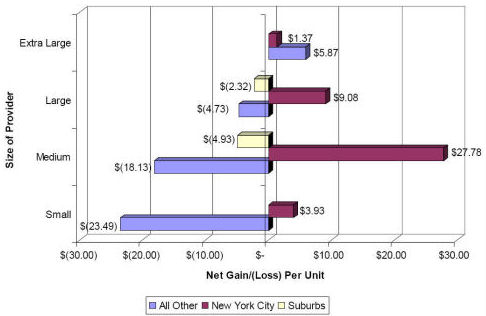

- Net gains and losses are heavily influenced by where a provider is located.

- Variations between providers costs and revenue indicate huge differences in how providers are controlling costs and billing revenue sources.

- The effects of size and location on provider costs and revenue vary and do not follow a consistent pattern.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Data Sources

NYS OMH has provided PCG with numerous data sources to help us capture the current landscape of Medicaid reimbursements. Some of the data received and reviewed by PCG are:

- Consolidated Fiscal Reports

- Medicaid Management Information System claims data

- Institutional Cost Reports

- Patient Characteristics Data

Each of these data sets is described more fully below.

Consolidated Fiscal Report (CFR) Data

The Consolidated Fiscal Report is a standardized accounting methodology and reporting tool. These annual reports collect financial and statistical data for providers that participate in the Medicaid program. The data represents both Article 28 (hospital based clinics) and Article 31 (free standing based clinics) providers that submitted a CFR for 2005. For this study, PCG analyzed calendar year 2005 CFR data for clinic, continuing day treatment and day treatment programs to identify revenue sources and service costs by cost categories. In 2005, there were approximately 455 New York agencies/programs that received Medicaid revenue for mental health services. Out of the 455 agencies/programs, we analyzed 346 programs from across New York State.11 Below is an overview of the 346 agencies and programs included in the study. Clinic treatment programs represent 62% of the providers included in this study.

Comparison of Types of Programs offered by Providers

| Region | Total Number of Programs | Number of Clinic Treatment Programs | % of Total Programs | Number of CDT Programs | % of Total Programs | Number of Day Treatment Programs | % of Total Programs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New York City | 132 | 88 | 66.7% | 33 | 25.0% | 11 | 8.3% |

| Suburbs | 56 | 33 | 58.9% | 18 | 32.1% | 5 | 8.9% |

| All Other | 158 | 94 | 59.5% | 50 | 31.6% | 14 | 8.9% |

| Total | 346 | 215 | 62.1% | 101 | 29.2% | 30 | 8.7% |

Agencies are required to report CFR data under the following categories:

- Revenue: Represents all revenue including third party revenue, grants and state and local net deficit funding.

- Personal Services: Represents cost of agency personal services related to program including support, direct care, clinical and program administration and LGU administration for programs.

- Fringe Benefits: Represents fringe benefits corresponding to personal services including FICA, retirement benefits, group life insurance, etc.

- Other Than Personal Services: Includes professional fees (i.e., accounting, payroll, legal, consulting, etc.), employment recruiting (i.e., advertising, employee referral fees, temporary office help, etc), supplies (i.e., general supplies, postage and shipping, cleaning, etc.), travel (i.e., airfare, training, vehicles, and conferences for program staff) and other categories that may be applicable.

- Property and Equipment: Represents cost incurred on all physical plant equipment (i.e., depreciation, interest, lease expenses, etc.) and property maintenance (i.e., repairs, insurance, taxes, utilities, depreciation building improvement, etc.).

- Administration: Represents expenses that are not directly associated to a particular program but rather to the broad management of programs, or maintenance for the agency, such as personnel that is not directly related to any particular program, service or contract.

Medicaid Management Information System (MMIS) Claim Data

The Office of Mental Health provided Medicaid Management Information System data to PCG with claims data by provider. The MMIS data include information such as service provider, county location, types of services, and specific services provided. They also include 2005 information about number of visits per service, base rate, COPs rate, Non-COPs rate, CSP rates and total rates charged per specific services. The data represent all claims paid by Medicaid for clinic treatment, continuing day treatment and day treatment programs.

Medicaid Payments by Type of Service

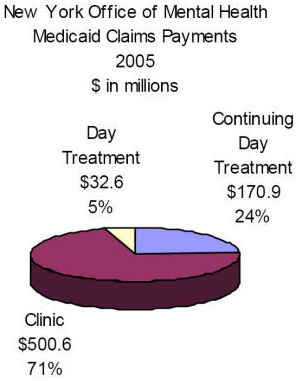

As shown in the graph, a review of the claim data shows that NYS OMH paid:

- $500.6 million (71%) for clinic treatment programs,

- $171.0 million (24%) for CDT programs and

- $32.6 million (5%) for day treatment programs.

These figures included Medicaid base rates, and COPs, Non-COPs and CSP add-ons.

Agencies/Programs by Type of Service

New York State Office of Mental Health

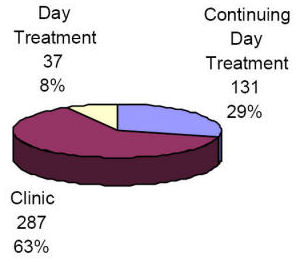

Number of Agencies/Programs That Received Payments from Medicaid 2005

As shown in the chart, there were a total of 455 agencies/ programs in 2005 who received Medicaid payments for mental health services. Of 455 programs, 63% were clinic programs, 29% were CDT programs and 8% were Day Treatment programs. The Medicaid data from all 455 programs confirms that clinics represent a similar percentage of programs as is presented in the CFR data for the 346 providers included in this study.

Institutional Cost Report

Institutional Cost Reporting (ICR) is used to report the total revenue and expenses to the Office of Mental Health by hospitals. ICR uses the most recent allocation percentages from the step down originated from the last Institutional Cost Report. At the time of this study, the most recent ICR is from 2002. The ICR data was not used for this study because the data represented 2002 costs and could not be accurately compared to other data sources from 2005.

Patient Characteristic Data

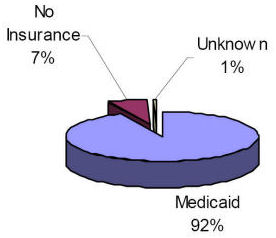

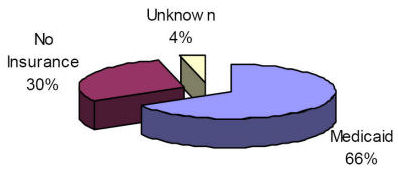

The Patient Characteristic data represents a snapshot of the number of consumers, type of insurance, age and diagnoses for consumers seen at mental health clinics during one week in a year. NYS OMH requires all providers to document an extensive list of characteristic for all consumers that receive services at the clinic for one week each year. The data used for this study was for the third week of October 2005, which was the most currently available. The Patient Characteristics data allowed PCG to better understand who mental health providers are serving. The data includes the consumers provider county, age and types of insurance.As shown below, the percentage of consumers with Medicaid was 65% for clinic treatment, 66% for day treatment and 92% for continuing day treatment. The patient characteristics file reviewed by PCG did not include insurance other than Medicaid or No Insurance. The designation of unknown in the graphs below represents clients that have insurance other than Medicaid.

New York State Office of Mental Health

Characteristic of Patient Population

Clinic Treatment

New York State Office of Mental Health

Characteristic of Patient Population

Continuing Day Treatment

New York State Office of Mental Health

Characteristic of Patient Population

Day Treatment

The patient characteristic file is also used to compile the consumer illness severity. The following chart shows that overall that 57% of the consumer population has a severe, persistent mental illness (SPMI - Adults) or serious emotional disturbance (SED - children).

| Program | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness Severity | Clinic | CDT | DT | Total |

| Non-SPMI / SED | 48% | 4% | 5% | 41% |

| SPMI / SED | 50% | 95% | 94% | 57% |

| Unknown | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Data Analysis

The intent of this section is to highlight differences in provider revenues and provider costs across similar and dissimilar provider types. There are material differences in revenues and expenses per unit across similar and dissimilar provider types. There is a strong correlation between how much the provider generates in revenue and how much that provider spends. In many cases, the more revenue the provider generates, the more costs the provider will incur. The opposite is also represented: the less the provider generates in revenue, the less that provider will incur in expenses. The analysis of per unit results shown later in this section of the report will highlight the correlation between revenues and expenses. The analysis will also demonstrate the wide variations between providers in cost and revenue.

The charts below represent total gains and losses incurred by providers for clinic treatment, continuing day treatment, and day treatment services. The chart demonstrates that current losses of $54.5 million for clinic treatment programs differ drastically from the $2.0 million loss in the Day Treatment program and the $5.9 million gain realized by CDT program.

Net Gains and Losses for All Mental Health Providers

All programs

Net Gain/(Loss) in $ millions

The differences in net gains and losses by program indicates a disparity in reimbursement strategies and cost containment by program. However, when taking a closer look at the net income and loss data, there are a number of providers that have significant deficits that are contributing to the high net deficit number, particularly in clinic treatment. These providers or net deficit outliers have the potential to skew the results which could lead to inaccurate assumptions concerning revenue, cost and net income. It is not known whether these outliers are due to data reporting problems or whether the providers actually incurred these gains or deficits. Therefore, it was decided to remove these outliers from all detailed financial analysis, particularly when analyzing per unit results. However, it is important to note the impact these outliers have on the overall results so that any decision or recommendations under consideration take into account these outliers.

The outliers for clinic and day treatment programs were determined by taking the top 5% and bottom 5% of all providers by program based on net gain. For day treatment, there are 30 programs in the study and two of the providers or 10% of the population was identified as having large net deficit amounts. The disparity between providers with net gains for day treatment were minimal and no providers were identified as net gain outliers.

The first table below shows the number of programs in each category and the second table displays the breakdown of net gain/(loss) in millions. A review of the clinic treatment results show that $48.6 million or 89% of the net loss outliers are attributable to 13 out of 215 programs while the net gain outliers of $12.8 million represent 11 programs. Overall 90% of the providers (191 programs) incurred a combined net deficit of $18.7 million or 35% of the total deficit.

| Number of Programs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic Treatment | Continuing Day Treatment | Day Treatment | |

| Net Gain Outliers | 11 | 5 | 0 |

| 90% of Providers | 191 | 90 | 28 |